“There is no new thing under the sun.” - Ecclesiastes 1:9

Humankind has made irrefutable technological process during our short tenure on this planet. We have manipulated the elements around us to propel ourselves to the top of the food chain, bringing with it a comfort of life and a plethora of capabilities that would’ve been thought impossible to our forebears. Despite this ingenuity, human nature has changed very little. Our biological makeup is nearly identical to those that traversed the earth before us. Our behaviour patterns, though disguised in niceties and etiquette, still draw from animalistic tendencies. We’re still plagued by the compulsiveness, greed and naivety that has gripped members of species since the beginning of time. Human nature really hasn’t changed.

We have all heard the aphorism that if we fail to study history, we are doomed to repeat it, and this holds even more true today. As our world is ravaged by war, as financial market participants are duped by fraud, as the stories with the same plot repeat themselves with an almost uncomfortable frequency, one has to wonder - do we ever learn?

I don’t have the answer to that question, nor will I try to pretend like I do. However, during my time trying to understand and participate in financial markets, I can’t help but notice how frequently large-scale frauds seem to occur.

Take ponzi schemes as an example, these heinous financial entities perpetrated by downright evil actors have victimized thousands of individuals across hundreds of years. Many would trace back their origins to Charles Ponzi, a man that defrauded an abundance of investors with promises of being able to generate 50% returns in 45 days. However, despite the importance of these events, and the name of the schemes since being attached to this bad actor’s name, there are actually earlier occurrences, ones that can be traced all the way back to the 1800s.

Arguably the earliest documented case of a ponzi was in Bavaria in the late 1800s. Our villain in this story is Adele Spitzeder, a German woman that turned to financial crime after retiring from a semi-successful career as an actress in the 1860s.

Accustomed to living a fairly luxurious lifestyle, when her income from her previous occupation approached the zero bound, she embraced the art of the grift rather than trying to cut expenses. Similar to Ponzi, Spitzeder devised a plan - concocting a recipe for an investment opportunity that promised to pay an unrealistic but enticing 10% per month. At the end of 1869, Spitzeder found her first victim, webbing her in with tales of spectacular potential riches. Enticed by her charm, this working class woman decided to invest, handing over 100 gulden to Spitzeder. Ruin was not instantly met. A short time later, the investor received 20 gulden back from Spitzeder, with the promise to receive a further 110 gulden three months down the line. As you might imagine, tales of spectacular and expedient profits rapidly spread, and Spitzeder quickly received investments from hundreds of people, mainly members of lower income classes who did not know any better. This demand was almost downright insatiable and soon, out of necessity, Spitzeder decided to open a bank in order to keep the scheme afloat - Dachauer Bank was formed. Like other entities set up to help sustain a fraud, their operations were all a front. Accounting procedures were minimal, and the deposits of incoming investors were stashed under floorboards, hidden in cupboards, and stored in other manners that were not befitting of a well-run financial institution.

Even despite operating in a manner that would give any auditor a heart attack, growth continued. The bank started to employ hundreds of contractors to keep the day-to-day running smoothly, was speculating heavily on real estate purchases, and was drawing an abundance of deposits away from Bavaria’s legitimate banking operations due to the high interest it offered (despite stealing customer principal). Withdrawals from legitimate banking operations to Dachauer bank eventually became such a problem that government officials took notice. The Minster for Upper Bavaria started to note the unusually high withdrawals that were being made from neighbouring banks, and became concerned with both the legitimacy of Dachauer Bank’s operations and how they were able to offer such enticing returns, as well how these happenings could potentially cause ripple effects through the rest of the economy.

Fearing economic calamity, government entities quickly worked to steer the ship right. The Interior Ministry placed ads in newspapers, warning customers not to invest, and the Munich police denounced the bank’s fundamental soundness - actions that added more fuel to the fire as investors deemed this a coordinated effort to deter working class individuals away from fantastic investing opportunities.

It didn’t help that Spitzeder’s philanthropic endeavours were widely cherished. Though financed with stolen money, she had opened nearly 12 soup kitchens, actions that not only elevated her in the public sphere, but also in the eye of the media. Coupled with the fact that she had also extended enormous loans to a plethora of newspapers, she was able to largely control the narrative.

Despite all of this, the hunches of competitors and government officials, coupled with the organized efforts of the courts to synchronize an enormous withdrawal of depositor funds, eventually lead to the bank’s demise. In 1872, after a group of 760 individuals demanded large sums of their money back, Dachauer Bank went under, unable to meet withdrawal requests with cash they had on hand. Shortly thereafter, the true nature of the bank’s operations were uncovered, and Spitzeder was sentenced to a measly 4 years in prison (by exploiting loopholes in the Bavarian legal system) for running one of the biggest frauds in history at the time, swindling an estimated €430M euros in today’s money away from investors.

Flash forward more than 130 years, despite undeniable progress made by our species in almost every field, a similar situation happened. Madoff likely needs no introduction. The man is getting a lot of resurgent attention of late due to the newly released Netflix docuseries, and for good reason, he perpetrated one of the largest frauds of our generation, one that infiltrated financial infrastructure to the very core, and showcased how fragile, poorly operated, and ripe for exploitation our systems are.

Madoff essentially operated in two spheres - one legitimate and one displaying all of the hallmark traits of a typical ponzi scheme. His brokerage firm on the legitimate side of things was rather impressive - technology that was created in-house was responsible for early foundations of the Nasdaq , and by the late 90s the man was processing close to 20% of the trading orders on the New York Stock Exchange. This prowess brought with it admiration and respect - Madoff operated in commendable circles, sitting as a chairman of the National Association of Securities Dealers, swaying regulatory direction with his interactions with the SEC, and more. In addition, similar to our predecessor outlined earlier, Madoff was known for his philanthropic side and sway outside of finance, existing as a major contributor to a plethora of charities and to the Democratic party of the United States. On the illicit side of things, Madoff wasn’t so rosy. Madoff Investment Securities also operated an illegal quasi-hedge fund/advisory business, one that leveraged ponzinomics to its benefit. The scheme was relatively straightforward. Madoff collected funds from clients with the promise of steady profits, displaying past results that showcased consistent performance to draw them in, often marketing a fake option “collar” investment strategy to the more inquisitive potential investors.

These claims were of course malarky. What Madoff was instead doing was depositing inbound client funds to a Chase Manhattan Bank account, paying out “returns” to early investors by using the money obtained from later investors. Though simple on paper, Madoff employed a host of individuals to spin a false web of sophistication around these happenings, with some employees spending hours a day fabricating documentation that outlined the firm’s fake trades. In reality however, the fund relied on a constant inflow of capital to keep the operations going. Old investors could be paid out consistently as long as new investors kept coming in. However, when the GFC hit and the music stopped playing, trouble emerged. In 2008, when the redemption requests started to hit, Madoff Investment Securities was unable to cover these withdrawals with the cash they had on hand. The scheme was then unearthed, Madoff was arrested and was sentenced to 150 years in prison for his actions. Madoff would later die of natural causes in prison last year.

Take Sam Bankman-Fried as another example. Although FTX was arguably not operating an identical scheme to Spitzeder and Madoff, his ascent shares many similarities. The since disgraced cryptocurrency figure started Alameda Research in 2017, a crypto hedge fund that rose to fame as a result of its supposed exploitation of the “kimchi trade” opportunity. In essence, due to the restrictive nature of the South Korean Won and Japanese Yen currencies, crypto that traded on exchanges housed in these geographical areas traded at a slight premium in comparison to other parts of the world. Traders could exploit this arbitrage opportunity by purchasing crypto in other areas, and sell it on South Korean or Japanese exchanges to capture the spread. Alameda Research supposedly just did that, garnering massive amounts of profits and growing their AUM spectacularly in the process.

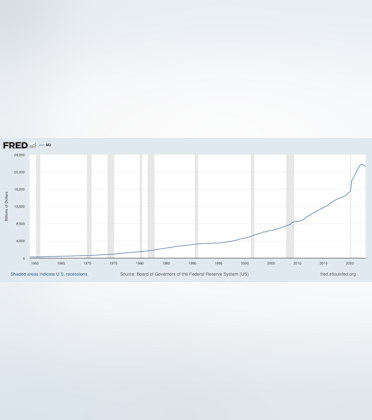

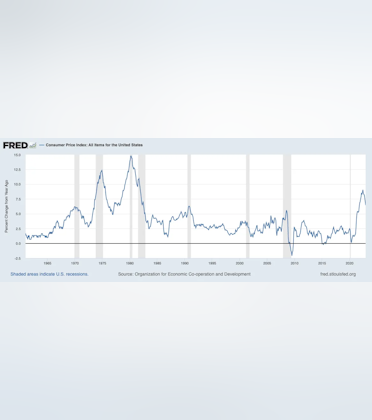

This newfound scale, in conjunction with the relatively underdeveloped nature of cryptocurrency infrastructure at the time, spurred SBF to pursue another venture simultaneously - the creation of a cryptocurrency exchange FTX. The endeavour made sense on paper, you had a trading firm on the left that wanted their trades to be executed in a better manner, so why not create a cryptocurrency exchange on the right that was capable of doing just that? The supposed technical prowess of the newly formed entity made its way into the mainstream crypto sphere, and the geeky nature of Sam quickly fooled investors into he was the next misunderstood tech genius that would bring with him swaths of riches. Venture capitalists, pension funds and other supposedly sophisticated investors participated in the nearly $1.8B in funding that FTX was able to obtain over the course of its short lifetime. With central-bank induced liquidity spurring on the most irrational of exuberances across markets, the FTX valuation soared in conjunction with the lofty ambitions for the cryptocurrency ecosystem as a whole, reaching almost $40B at its peak. Hoards of cryptocurrency hedge funds, cryptocurrency enthusiasts, and mom and pop investors deposited their assets on the platform, a value that reportedly reached approximately $16B at its peak. SBF started to become revered by mainstream media. His philanthropic endeavours resulted in many stating SBF was going to change the world. Even after the monumental scandal was uncovered, the Wall Street Journal still had the audacity to tout how fraud ruined the man’s plans to save Planet Earth:

In addition, SBF was also consistently lobbying with politicians to bring regulation to the crypto space, and was the second largest contributor to the democratic party ahead of their most recent election, next to the legendary George Soros.

Monumental ascent aside, the descent was even more spectacular. Giving WeWork a run for its money, the evisceration of valuation and capital was truly astounding. Spurred on by a piece created by Coindesk that speculated that FTX’s balance sheet wasn’t as solvent as some might believe, as well a social media storm created by Binance outlining that they were selling their holdings of FTX’s native token, a bank-run-esque situation came into fruition.

In essence, these happenings outlined the fact that a key component of FTX’s balance sheet was made up of their native tokens, FTT. Put simply, the company created, out of thin air (using code), “assets” that were at their core inherently worthless, but after being touted to the masses during FTX’s phenomenal rise, saw an equally remarkable trajectory upwards. Marking these tokens to market allowed for FTX’s asset position to be bolstered significantly, which on the surface may have resulted in the company appearing solvent when in reality this was far from the case.

Spurred on by the aforementioned media frenzy that occurred in the latter half of last year, investors started to run for the doors. Similarly to other financial schemes, once it was found out that the company did not have the sufficient assets to pay back their customers, they quickly went under. Shortly thereafter, FTX was arrested in the Bahamas and is now on trial, the outcome of which will be very interesting to monitor going forward.

Spurred on by the aforementioned media frenzy that occurred in the latter half of last year, investors started to run for the doors. Similarly to other financial schemes, once it was found out that the company did not have the sufficient assets to pay back their customers, they quickly went under. Shortly thereafter, FTX was arrested in the Bahamas and is now on trial, the outcome of which will be very interesting to monitor going forward.

Frauds like these are bound to continue to occur. Investors would be best served to extensively research any and all investment opportunities they participate in, and remember that if something sounds too good to be true, it almost always is. Although focus on the present moment is undoubtedly important, the study of history ensures we are not duped by the same tactics of the past.