Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Extended Preview - $CPRT Deep Dive

“Of all Elixirs, Gold is supreme and the most important for us. Gold can keep the body indestructible. Drinkable gold will cure all illnesses, it renews and restores.” - Paracelsus

Chemistry has a medieval ancestor known as alchemy, a field of study that pushed forward the scientific field quite substantially in between the middle ages and the 17th century. One of alchemy’s most sought after endeavours was the obtainment of the philosopher’s stone, a substance that alchemists believed would be able to turn base metals into precious ones, particularly gold and silver. In addition, alchemists believed that the philosopher’s stone contained physical properties, commonly known as the elixir of life, conferring longevity, bodily rejuvenation, and potential immortality to anyone that drank it.

Although the scientific legitimacy of this pursuit has been debunked (not writing it off entirely, our species is full of innovative creatures), it does highlight something engrained within the human condition, what I will denote as the “something from nothing” phenomenon. Within markets, individuals are often attracted to the loudest voices, buying into endeavours that are often too good to be true. Past frauds from the likes of Charles Ponzi to Bernie Madoff gripped the masses, fooling individuals that were intelligent on paper with promises of phenomenal returns across all time-frames. Even recently, the recent FTX debacle highlights the degree at which even the most supposedly sophisticated of investors (Sequoia, Ontario Teacher’s Pension Plan, etc.) were gripped by promises of riches, forgoing due diligence and succumbing to FOMO. In short, much like the philosopher’s stone, we all want to turn nothing into something. We are all enticed by the promise of being able to turn the invaluable into gold.

Being that as it may, sometimes someone does find a way to create immense value out of things that others would scoff off entirely. Copart is one of those instances. Copart turns junk into gold.

But how exactly does Copart’s philosopher’s stone work?

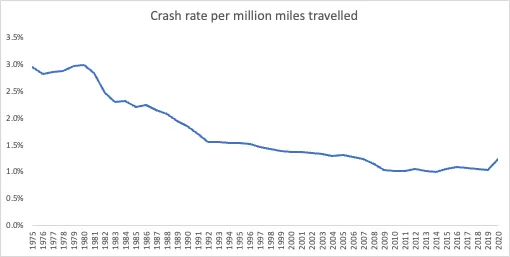

In the US alone, the last five decades has seen the moving 12-month total of vehicle miles traveled more than double from approximately 1,292,257 millions of miles at the beginning of 1975, to approximately 2,873,804 miles at the beginning of 2022. Intuitively, this makes sense. With steady population growth and consistent rates at which individuals direct expenditures at obtaining and maintaining the right to operate a motor vehicle, it is only natural that the total amount of miles traveled increases over time, especially as the desire to remain mobile remains ingrained in our cultures. With an increase in miles driven, a steady rate of accidents has also occurred. Per IIHS data, the crash rate per millions of miles traveled has plateaued over the last few years in the low one percent range, a phenomenon that is likely to remain consistent given human nature and the recklessness that is embedded therein, even despite the safety improvements that have been made with vehicles over the last couple of decades:

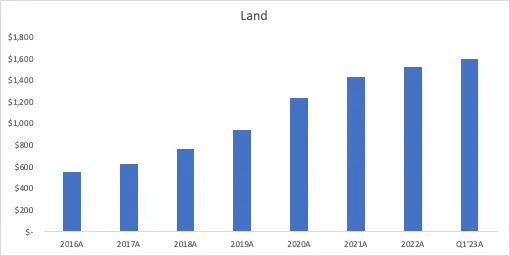

Copart’s business is tied directly to these car wrecks. In order to understand why exactly this is the case, we have to start breaking down each component of Copart’s business separately. Let's start from the ground up, literally. As of their most recent annual conference call, the company has approximately 16,000 acres of land, of which house thousands of salvage yard facilities:

Therein, the salvage yards contain rows upon rows of vehicles, of which the two key parties of the Copart business model, the buyers and the sellers, would like to interact with in some way shape or form, either to get a vehicle off of or on their hands. Vehicle sellers are primarily insurance companies, but also include the likes of banks, fleet operators, rental companies, individuals, etc. Vehicle buyers on the other hand are primarily vehicle dismantlers, used vehicle dealers, exporters, and again, individuals.

Let’s use a typical accident as an illustrative example to see how one can interact with the yards themselves. When a car accident occurs, damage to the car may range from a minor scratch to the more severe, and one will typically wonder if their insurance will be able to cover the repairs, or if they will even deem it worthwhile to do so in the first place. After the damaged car has been transported to a temporary storage facility, the insurance company will enlist the services of a claim adjuster in order to assess the vehicle. The claim adjuster will determine the actual cash value (commonly known as the pre-accident value outside of Canada) of the vehicle, which is essentially the replacement value of the vehicle less any accumulated depreciation. If the sum of the cost to repair the vehicle, the vehicle’s salvage value, and the cost to provide the driver with an interim means of transportation is more than the actual cash value, the vehicle will be deemed a “total loss”. If the opposite is true, and the aforementioned total is less than the actual cash value, the insurance company will usually decide to go forward with the vehicle repairs. Copart becomes involved with the process if the car is deemed a total loss. Once this is the case, the vehicle will then be towed from the temporary storage facility to a salvage yard. Thereafter, the insurance company (the seller in this case) will await the vehicle to go through the process of being sold at auction and have its title transferred (usually the longest part of the process depending on how expedient the DMV is, can be expected to take ~30-45 days). Upon completion, they will settle with the insured individual.

In the United States and Canada, and occasionally in other International Markets, the company will operate as an agent, providing remarketing services and selling salvage vehicles on behalf of the insurance companies (or other sellers) on a consignment basis. As alluded to earlier, this is not always the case in international markets. Sometimes Copart acts as both a principal and an agent. In the UK, since insurance companies there are less likely to want to take on auction price risk, Copart will act as a principal and purchase the salvage vehicles outright, reselling the vehicles directly from their balance sheet. As an additional example, in markets such as Germany, vehicles are often listed on behalf of insurance companies, whereby the insurance companies will leverage the platform to payout the insured the actual cash value less the highest bid. The insured, upon receiving the payout from the insurance company, will then have the option to accept the highest bid, or the bid of another third party received within a few weeks of the original auction.

...

The remainder of my article can be found at https://mtcapital.substack.com/p/copart

IIHS-HLDI crash testing and highway safety

Fatality Facts 2022: Yearly snapshot

A yearly snapshot of fatality statistics compiled by IIHS from 2022 Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) data.

Already have an account?