Taming the dragon

Economics | Chinese de-leveraging

China’s heavily indebted real estate market threatens to burn down the economy. Will government stimulus be enough to save it?

•••

Chinese real estate developers have been dropping like flies. They spent the last few decades binging on debt and are loaded up with it. The country is now battling to prevent debt deflation, where asset prices fall as debts rise. Can China stop the economy from circling the drain and avoid a deflationary spiral? The answer will depend on whether the government can prop up the real estate market enough.

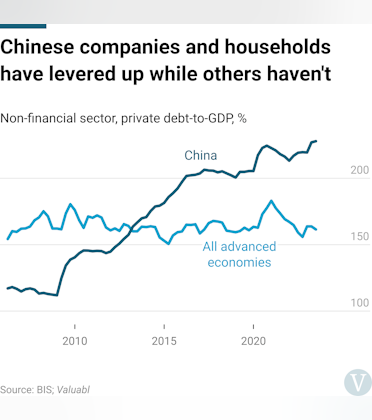

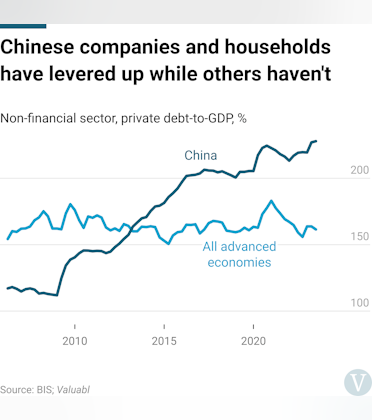

The Chinese economy is drowning in debt. The country's debt levels are dizzying but stagnant. Private sector borrowings are a whopping 228% of gross domestic product (GDP). Most of which is on corporate balance sheets—non-financial companies owe 166% of GDP.

Borrowing more and more was a standard part of China's playbook. The government, wanting to boost asset prices, encouraged everyone to do so. But houses got too expensive, and many families couldn't buy. The government wanted to change that. So, in August 2020, it introduced the Three Red Lines policy to rein in real estate borrowers and lenders.

That policy restricted how much money developers and banks could borrow and lend. Yet, developers relied on an ever-increasing debt model. They and their customers needed the ability to borrow ever-increasing amounts. Without it, they've felt the pinch.

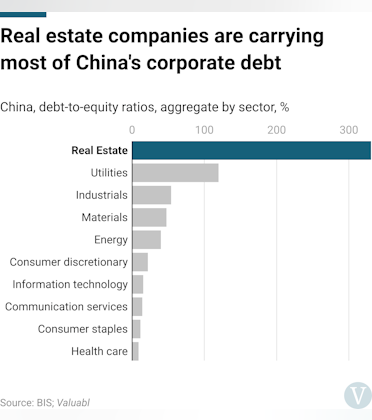

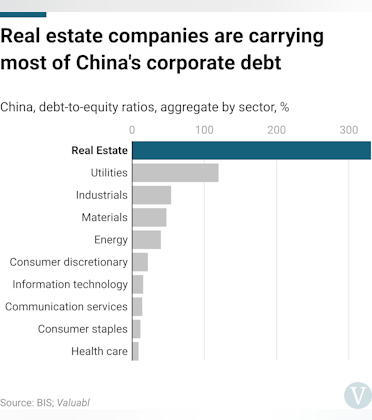

Now, Chinese property firms are struggling. There are two reasons for this. First, they're stunningly levered. Chinese real estate firms are responsible for most of the country's corporate debt. The total debt-to-equity ratio for the sector is 330%, much higher than the 31% total for the non-real estate sector. By comparison, American real estate companies are at 75%, and the global total is 109%. Second, profitability has tanked, pressuring their ability to repay. Developers' returns on equity have fallen to -5 %, while all other sectors are doing fine.

Chunky losses have squeezed developers' ability to repay their lenders, and many are now in default. A massive $125bn of bonds are now in default across China's $175bn dollar-bond market. Struggling real estate firms are a sign of property market struggles. If asset prices fall as developers close up shop, credit will collapse. That could trigger a long and painful debt deflation.

The Chinese have felt these tremors across their economy. The housing market has started to crack as the impact of deleveraging hits. House prices have fallen 8% from their 2021 peak, while new home prices are down 12% since last year's first quarter. Property investment has also dropped 9% in the past year. Falling property prices make home shoppers and investors less keen to jump in. That, in turn, pulls down prices and new home sales, putting developers and sellers under more pressure and forcing them to sell assets to raise cash.

Mainlining stimulus

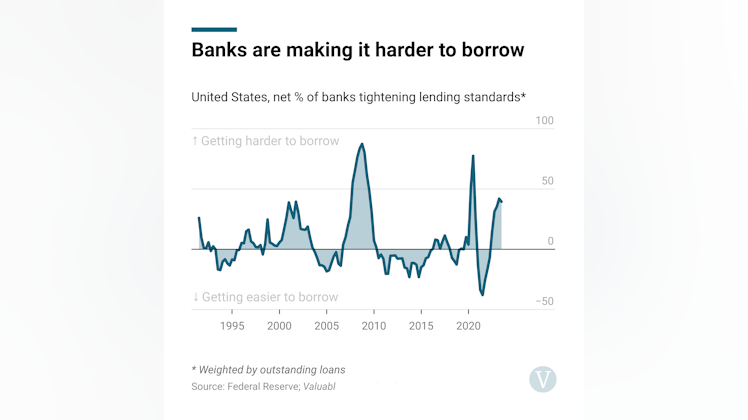

Xi Jinping, China's leader, has rolled out his stimulus gun to defend the economy from the debt deflation dragon. The government will provide 1trn yuan ($137bn) for affordable housing and urban renovation. The People's Bank of China, the country's central bank, will shoot this low-cost money into the economy in phases using the country's banks. The money will fall on households to prop up home prices and sales volumes. This 16-point plan, as they've called it, will reverse most of the credit tightening that the Three Red Lines policy caused. It will make it easier for everyone to borrow for real estate.

The government won't stand by as the property market burns—stimulus was always on the way. China's real estate market is too big to fail. It's the driver of the country's economic growth and household wealth. Property is 30% of China's GDP, making it the biggest contributor to the world's second-largest economy. According to the China Household Wealth Survey Report, real estate is also responsible for 70% of household wealth, as Chinese families have limited investment options. There are too many people in too big an economy for the country's leaders to stand by.

It'll be challenging to tame China's debt dragon. But, if the government can prop up the real estate market long enough, the tide will turn, and the sector will re-inflate. If not, it's all fire and brimstone for the foreseeable future. ■