Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Trending Assets

Top investors this month

The Hard Truth About Aging: Losing Your Fastball

"Everyone, at everything, eventually loses their fastball. The trick is figuring out what to do next"

As a long-tenured investor stumbling closer to the age of 60, I feel duty-bound to inform the younger investor what might lies ahead in the far-off horizon. Think of this as a preview of things to come. I hope a lot of investors under the age of 35 read this essay, then there’ll be no surprises when you find this out for yourself. You can embrace and plan for it. It might even influence some of the longer term decisions you make today.

It’s fortunate that our skills in the field of investing and trading can be sustained for multiple decades. We don’t suffer the short "peak life" that track and field athletes typically experience for example. They peak around the age of 25 to 28, and then face a pretty daunting drop off. Despite the long "shelf life" of an investor, there eventually comes a time when the fastball analogy comes into play. We have to accept that as we age, our cognitive skills start to deteriorate. We also begin to lose touch with the dynamics of the stock market because we become "generationally separated" from the emerging industries driving the economy. I struggle to grasp the full ramifications that machine learning, AI and collaborative robots will have on business. I have zero interest in the metaverse. I’m no longer in the workplace to experience those shifts first hand. Once you retire from the workplace, your social circles begin to contract and it becomes challenging to keep abreast of new technologies. We're too busy curating our suburban lawn so we can yell "get off my lawn" at the neighbourhood kids.

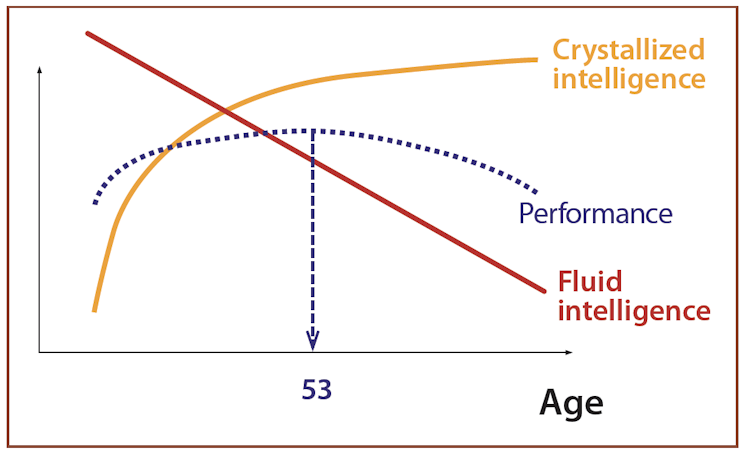

According to research published by Professor David Liabson of Harvard University, there are 2 categories of intelligence:

Crystallised Intelligence: This is our ability to solve familiar problems because of our accumulated knowledge and life experience. We become better investors with more experience and wisdom.

Fluid Intelligence: This is our ability to confront and solve novel problems. Fluid intelligence helps us learn new things, grasp complex concepts and engage in abstract thinking.

Crystallised and fluid intelligence are countervailing trends. Cognitive research has found:

- A person’s ability to solve problems peaks around age 20

- As we approach midlife, our gradual decline in problem solving ability is counter-balanced by an increase in "crystallised intelligence", meaning our wisdom compensates for our worsening problem-solving skills.

- Unfortunately, there are limits to how much wisdom can compensate for declining fluid intelligence. We tend to reach those limits at age 53 (bad news for me, I’m skiing the downhill slope).

- After your 50s, a decline in fluid intelligence becomes the dominant factor for most people. The ability to make sophisticated decisions begin to decline.

- By the time we’re in our 80s, our ability to make good decisions is significantly compromised, particularly decisions for complicated unfamiliar problems.

Aging is a difficult reality to face. We first see the adverse effects of aging in our grandparents, then our parents. It’s easy to push the inevitability of our own aging into the dark recesses of our mind and dismiss it as a far away problem. But most of us are committed long-term investors. We've conditioned ourselves to think long-term and unfortunately, this means we should also think about our mental fragility as we age. The rate of cognitive decline will be different for everybody, but like taxes, there’s no avoiding it. There’s truth to the cliché "failing to plan is planning to fail".

The following graph plots the growth and subsequent decline of our cognitive function:

This is a sombre research finding, but not surprising.

"What you have to do is come to terms with the reality of this kind of data and recognise that you just can’t count on cognitive functioning to be at a high level over your entire life"

Professor David Laibson

When you’re a young high achiever, it’s easy to sustain long periods of intense focus. Learning new skills, thinking on your feet, synthesising new ideas and juggling multiple tasks comes naturally. You can juggle the demands of your day job and also trade off a fair portion of your leisure time to focus on building your wealth. Your natural competitive instinct kicks in and you choose to construct a portfolio of individual stocks to outperform the market index. Market averages just won’t cut it, you know you’re better than average. You commit your time, effort and intense focus to uncover those potential 100-bagger stocks just waiting to be discovered.

"The person that turns over the most rocks wins the game. And that's always been my philosophy"

"With investment, the person who works hard, spends their time on research and analysis of the stocks to find a good one at cheap price will make big profit"

Peter Lynch

As you head into your thirties, your passion for the stock market never wanes. But life comes at you fast and you get married, save for your first house, have kids and think about their futures. Decades start to pass quickly and then you start to notice a few things. It’s subtle at the beginning and you might laugh it off. But the signs become more frequent.

"By the time you are fifty, your brain is as crowded with information as the New York Public Library. Meanwhile, your personal research librarian is creaky, slow, and easily distracted. When you send him to get some information you need- say, someone’s name - he takes a minute to stand up, stops for coffee, talks to an old friend in the periodicals, and then forgets where he was going in the first place. Meanwhile, you are kicking yourself for forgetting something you have known for years. When the librarian finally shows back up and says, 'That guy’s name is Mike', Mike is long gone and you are doing something else"

Professor Arthur Brooks

Harvard Business School

Cognitive load starts to take its toll. The graph of our decline in fluid intelligence is only an average. Even so, mild cognitive decline doesn’t impair your day-to-day functioning, you just start noticing you don't think as fast and as well as you used to. Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger are both in their 90s and are still very lucid and competent in the affairs of investing. But they might be the outliers. It’s dangerous to assume you’ll be at the same level as them at that age and fail to prepare for your own eventual drop-off in cognitive skill.

Our acumen as stock investors remains intact longer if we practice continuous learning. But I can confirm that learning new things becomes downright difficult as you get older.

"If you’re experiencing decline in fluid intelligence, it doesn’t mean you are washed up. It means it is time to jump off the fluid intelligence curve and onto the crystallised intelligence curve. Those who fight against time are trying to bend the old curve instead of getting onto the new one. But it is almost impossible to bend, which is why people are so frustrated, and usually unsuccessful"

"So here’s the secret, fellow striver: Get on your second curve. Jump from what rewards fluid intelligence to what rewards crystallised intelligence. Learn to use your wisdom"

Professor Arthur Brooks

Harvard Business School

Your greater crystallised intelligence is the resource that helps you become much better at fusing and combining ideas. It’s harder for you to come up with new ideas, but you can draw upon your vast library of wisdom to better apply the concepts you already know. You become better suited to teaching, mentoring and occupations that rely on "soft skills". It’s just unfortunate that fundamental stock analysis draws more on your fluid intelligence.

I’ve personally found it difficult to sustain my own focus crunching the numbers and conducting the same level of in-depth due diligence that I used to for individual stocks. I’m gradually finding my process of stock ideation, prospecting, evaluation, selection and monitoring is becoming too onerous. My battery of cognitive energy is like an aging iPhone battery: quick to discharge and slow to recharge. There’s no such thing as a rapid charger at my age. If I take a nap, I come back at half capacity. A full nights sleep is needed for a full recharge.

I’m also afflicted by the willingness aspect. Quite frankly, I just can’t be bothered anymore. I might be combing through the balance sheet of a stock and then suddenly something on the TV captures my attention. Then I’ll want to look up something on the internet. A few hours later, it's bedtime and I haven't done my due diligence. This procrastination might be linked to my struggles with declining fluid intelligence, but now that I’m retired, I want to spend my available cognitive energy on new pursuits like studying architecture, art and design. These are subjects I never appreciated when I was younger, but now I find myself very intrigued to learn about them. I have the luxury of taking my time and working at my own pace. If I misunderstand or don’t get the concepts, it’s not going to be a costly mistake that risks my livelihood like buying bad stocks.

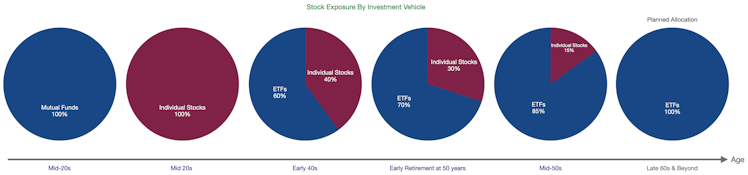

This has profoundly changed the way I invest. Whenever I sell out of an individual stock because I it’s slipped into secular decline, I no longer replace it with a new stock. Instead, I invest the proceeds back into my core market index and smart-β funds. From the 30 individual stocks I owned when I first retired at age 50, I’m now down to 15 (7 years later). That’s still a lot, but I expect it’ll be whittled down further.

One of my previous posts talked about how conditioned volatility composure allowed us to transition to early retirement with a portfolio comprising 90% stocks and 10% cash. This stock portfolio is now predominantly ETF-centric. If I’ve chosen well, they’ll require minimal attention, freeing up my time to spendo n other pursuits … including time to watch Netflix, read books and sitting in quiet cafes drinking coffee while watching other people hurriedly trying get to work on time. Of course I’ll still be reading about the markets and checking my portfolio every day. I’ll also jump on any opportunistic trades I see, provided all my entry-rules are satisfied. I haven’t found trading based on technicals to be cognitively draining at all.

"The most important thing as an individual investor ages is to start to simplify things. Because as we age, we lose the flexibility in our brains to make complex decisions, especially if we need to make them quickly. And so, by buying more simple investments, staying away from complicated private placements and things like that is really smart. The other thing is, it's really important to police yourself ... people need to understand themselves early, start policing themselves in their 50s or early 60s before they develop problems, understand how the brain works"

Dr Carolyn McClanahan

Co-founder of wHealthcare Planning

If I use a timeline to track our exposure to individual stocks, we seem to be going full circle:

We started off fully invested in mutual funds in the late 80s. As our knowledge about stock investing grew, we sold our underperforming mutual funds and blazed into a portfolio of individual stocks. When our portfolio inevitably started to lag market returns, we scaled up our allocation to market index and smart-β ETFs.

Today, our allocation to individual stocks is dwarfed by our ETFs. We’ll eventually end up exclusively invested in market index and smart-β ETFs. It’s a reflection of the circle of life. You enter this world wearing nappies, you leave wearing nappies.

Everyone experiences aging differently. How you adapt your strategy to deal with it will be your own preference. Just realise you won’t be the same person in your 50s that you were in your 20s and 30s. A decline in fluid intelligence might just be the trigger that changes the way you invest. The other trigger might be a reluctance to continue doing the same level of due diligence you did in your younger years. Your investing behaviour will evolve with your life stage. Here are some ideas to ease that transition:

- Shift to a more passive strategy. Then go out an enjoy life.

- Leverage the Pareto principle and condense your own investment process, focusing on only the most important metrics. I tend to treat each individual stock as a long-term trade. I do a scaled down version of business due diligence and rely more on technicals these days.

- Consider outsourcing your stock research to quality, trusted provider who can do all the leg work for you (prospecting, curating, researching and number crunching the stock opportunities). The cost is going to be well worth it. You’ll want to make sure you're presented with both the good and the bad aspects of a business so you can use that output to formulate your own conclusions, which may or may not agree with their recommendation. What’s important is that you make your own assessment and build up your own conviction. If you rely on their conviction, you’ll probably waver whenever the stock price comes under pressure. Maybe even consider subscribing to friends of this platform @stockopine, their analysis is very comprehensive and thorough. It's better than a lot of the very expensive subscription services from high-profile institutions we've subscribed to in the past.

You owe it to yourself to think about your "way-out-there" future in your strategic life planning.

Already have an account?