Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Interest rate holes in the hull

Can higher interest rates cause higher inflation? Paradoxically, yes.

•••

“Man using a drill to create a hole in the bottom of his boat” created by OpenAI DALL•E 2

Economic lore tells us that the remedy for high inflation is to push up interest rates. Higher rates, economists say, limit lending and pull prices down. But the relationship is more complex than that. Higher rates can create inflation if there’s much debt. Workers demand raises to cover their mortgages. Companies hike prices to maintain profitability. And the government’s increased interest payments create new money.

Jerome Powell, the boss of the Federal Reserve, finds himself trapped between a rock and a hard place. He wants to increase rates to snuff out inflation. But rate hikes are a blunt tool and might even make inflation worse.

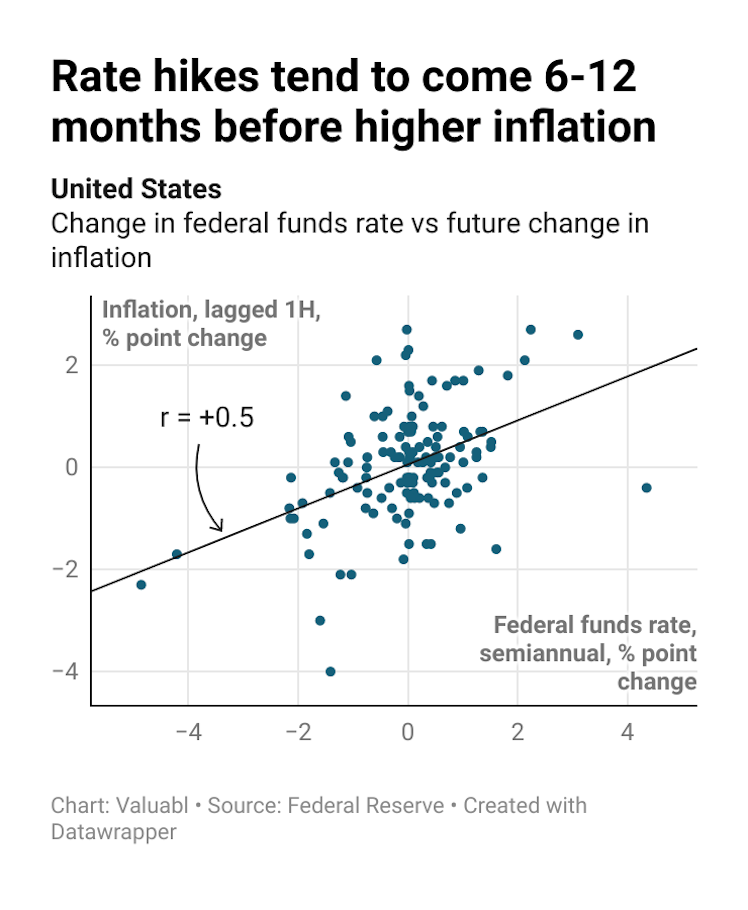

First, when rates rise, businesses pay more to borrow. A higher interest bill makes them lift prices to maintain profits. Price increases create inflation and lead to higher rates again. Federal Reserve data from 1955 shows that inflation tends to rise a year after the bank hikes. It could be that central bankers raise rates before inflation picks up. But that means rate hikes don’t work fast enough.

Second, elevated rates make mortgage and loan payments rise. Workers, squeezed by tighter budgets, push for pay raises. And businesses lift prices to cover the higher labour cost, creating inflation. The correlation between rate hikes and wages (+0.3) is less than consumer prices (+0.5), but it’s still there. Worker pay usually goes up within a year of rate hikes.

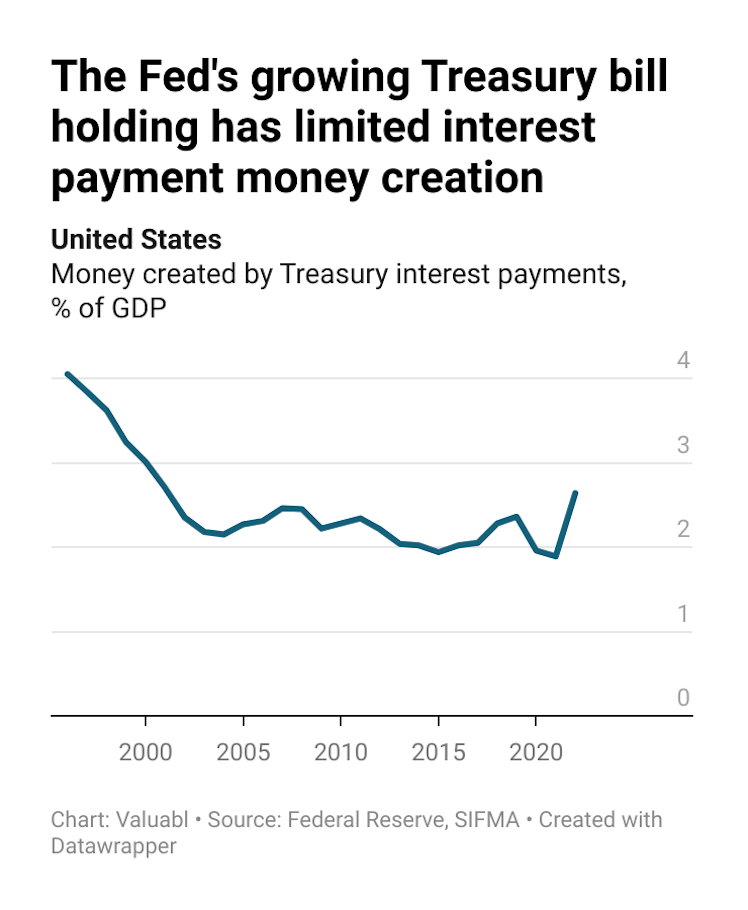

Third, higher rates make the government’s interest bill go up. Those interest payments create new money if the private sector owns the bonds. As the Fed pays its profits back to the Treasury, the state pays itself when it pays interest to the central bank. The right hand gives to the left—no new money. But if the private sector owns the bonds, the state creates money to pay the interest.

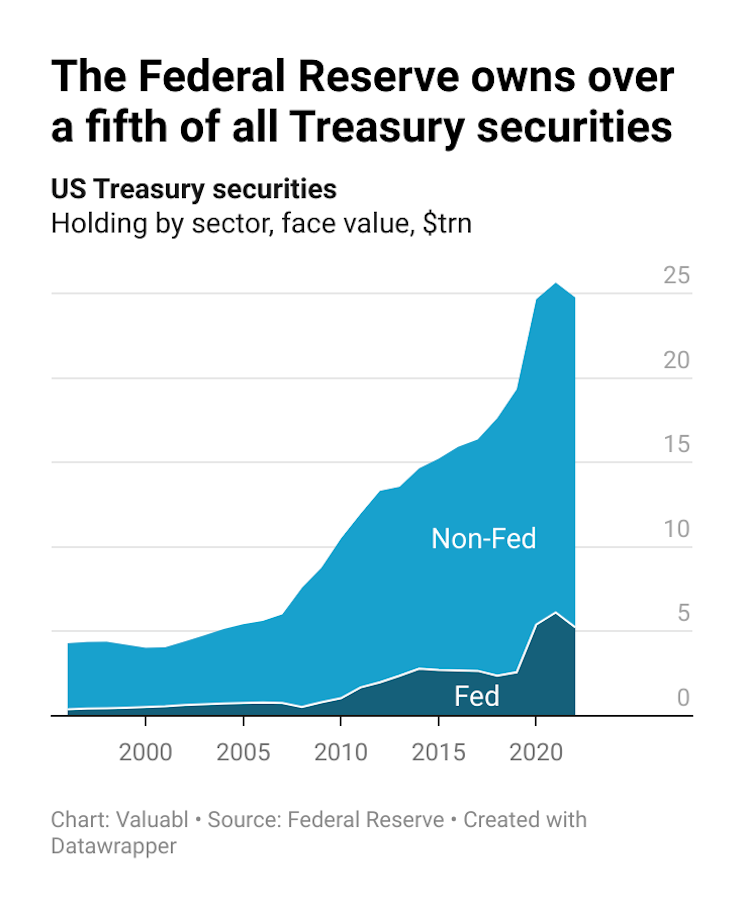

SIFMA, a financial industry group, estimates the Fed holds a fifth of all Treasury bonds. That means 80% of the state’s interest payments, which are now $853bn per year, go to the private sector. That’s $682bn, or 2.6% of GDP, of new money per year.

The relationship between interest rates and inflation is complex. When the central bank sells bonds, a process called quantitative tightening, rates go up. Economists reckon this cuts inflation. But if that pushes bonds into private hands and rates rise, the state creates more money to pay the interest. That adds to demand.

Currently, the Fed owns a large percentage of Treasury bonds. In 1996, for example, it held 9% compared to the 20% it has now. That growth capped the past impact of higher interest rates on money creation.

Jerome is stuck. If he sells Treasuries, rates will go up, and the state’s interest bill will stimulate demand. If he buys bonds, rates will drop, and the interest bill won’t add to demand. But this goes against economic orthodoxy.

The boat is filling up with water. Instead of plugging the leak and bailing water over the side, Jerome is drilling new holes to let it out.

Good luck with that.

Already have an account?