Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Trending Assets

Top investors this month

A Sign of a Looming Recession (And Maybe a Soft Landing?)

Last week, JPMorgan held its Q2 earnings call. The biggest takeaways you’ll see in the headlines are that the bank (1) set aside another $428 million for potential loan losses, (2) saw profits slip by 28% compared to last year, and (3) paused its share buyback program.

When the country’s largest bank sets aside more money for potential losses, it’s typically not a good sign. But it’s not as grim as it seems.

Yes, $428 million is a lot of money, but it’s not like JPM is sweating over it — this reserve allocation, which functions like an expense on their P&L, pales in comparison to the company’s net income of $8.6 billion.

Moreover, taking a step back, let’s quickly cover why JPM had to set more money aside.

In response to the financial crisis in 2008, legislation was passed to insulate the country’s financial system from another cataclysmic collapse. Nowadays, banks are required to hold a certain amount of capital to serve as a quasi rainy day fund — if the economy starts to spiral, the banks can keep servicing people, businesses, etc.

Every year, the Fed assesses the country’s largest banks’ ability to withstand a “severely adverse scenario” by running models with some pretty draconian assumptions. Here are the assumptions for 2022:

The supervisory severely adverse scenario is characterized by a severe global recession accompanied by a period of heightened stress in commercial real estate and corporate debt markets. The U.S. unemployment rate rises 5.75% from the starting point of the scenario in the fourth quarter of 2021 to its peak of 10% in the third quarter of 2023. The sharp decline in economic activity is also accompanied by increases in market volatility, widening of corporate bond spreads, and collapse in asset prices, including a nearly 40% decline in commercial real estate prices. The international component of the scenario features deep recessions in four countries or country blocs followed by declines in inflation and large swings in the value of the U.S. dollar against those countries' currencies.

The results of this year’s test? Even in a worst-case scenario, the aggregate capital ratio of the 34 largest banks — essentially, their equity capital compared to their risk-weighted assets — would more than double the minimum capital requirement (9.7% vs. 4.5%).

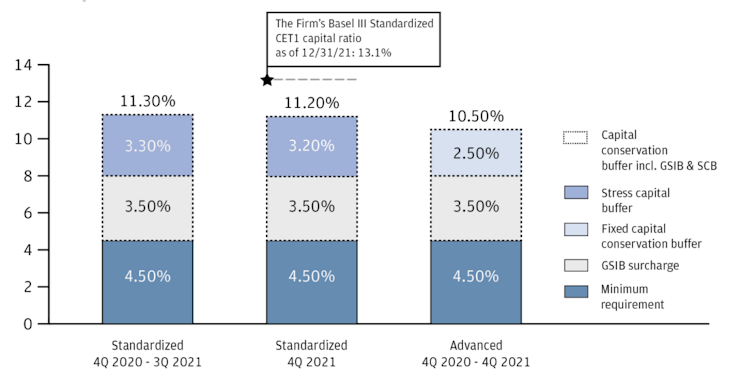

However, the global systemically important banks (GSIBs or “too big to fail” banks), such as JPM, are held to a higher standard. On top of the minimum capital ratio of 4.5% and a stress capital buffer (SCB), the GSIBs have a capital surcharge.

For a good visual overview, here’s how JPM’s capital ratio at the end of 2021 stacked up against regulatory requirements (in short, it did well).

Except JPM’s SCB and GSIB surcharge are going up — on the company’s earnings call, they estimated a total capital ratio target of 12.5% for Q1 2023. As of last quarter, JPM’s standardized capital ratio was 12.2%. So, they have to set even more money aside for potential losses.

Long story short, the reserve increase shouldn’t be construed as a signal to panic. At least, not yet.

Here’s some insightful commentary from JPM CEO Jamie Dimon:

“Consumers are in good shape. They're spending money. They have more income. Jobs are plentiful. They're spending 10% more than last year, almost 30% plus more than pre-COVID.

Businesses, you talk to them, they're in good shape. They're doing fine. We've never seen business credit be better ever, like in our lifetimes. And that's the current environment.

The future environment, which is not that far off, involves rates going up, maybe more than people think because of inflation, maybe stagflation…there might be a soft landing.

I'm simply saying, there's a range of potential outcomes from a soft lending to a hard lending, driven by how much rates go up, the effective quantitative tightening, defective volatile markets.”

Already have an account?