Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Trending Assets

Top investors this month

What I Learned from Trading: An Individual Stock Investment is a Long-Term Trade

Trading coach Dr Van Tharp has one particular doctrine he consistently reiterates in his books and training material:

"You don’t trade or invest in markets - you trade or invest according to your beliefs about the markets"

Dr Van Tharp

Trade Your Way to Financial Freedom

Admittedly I didn’t think about it very deeply when I first came across this statement, but it must have been notable enough for it to remain in the back of my mind . Thinking back, it probably explained why I flip flopped from one strategy to another as a young novice investor. Beliefs are usually forged from your influences and cumulative experiences. When you first start out, you might adopt beliefs about the stock market from the books and blogs you read (or the TicTok videos you watch). But book smarts don’t stick like street smarts once you learn from life experience. You might experiment with different investment styles in an iterative trial and error approach until you find one that sticks. Those experiences will shape your investing preferences until they become a good fit with your personality type. Until you settle on a solid investment philosophy as your bedrock, you’ll continue to make ad-hoc, knee-jerk changes whenever times get challenging.

"You must discover your beliefs about the market so that your system will fit those beliefs. You must know yourself well enough to develop your personal objectives and a system that fits those objectives"

Van Tharp

Trade Your Way to Financial Freedom

I’ve said before that the investor journey is a personal development journey. You have to know yourself and know your core beliefs about the market. Those beliefs may be differ from the beliefs of other investors. This is perfectly fine because if there’s one thing I’ve learnt during my 35+ years in the markets, it is this:

"The market will reward a diverse range of investment styles … just not all at the same time"

The Jazzi Cat Team

Every positive-expectancy investing and trading system will experience peaks and valleys. Investors and fund managers who use factor strategies (value, growth, momentum etc) will be familiar with this. The value factor underperformed growth for a good decade until it came storming back during the last couple of years. Investment styles swap in and out of favour with the ebbs and flows of the market cycles. I find the persistent disputes and sniping in social media about the optimal way to invest to be futile and unproductive. A system that maximises return might not suit many investors because the volatility and paper drawdowns you’ll be forced to endure might be too devastating. Wesley Gray of Alpha Architect published a research paper titled "Even God would get fired as an Active Investor" to prove this exact point. He concludes:

"Our bottom line result is that perfect foresight has great returns, but gut-wrenching drawdowns. In other words, an active manager who was clairvoyant (i.e. "God") and knew ahead of time exactly which stocks were going to be long-term winners and long- term losers, would likely get fired many times over if they were managing other people's money"

Your beliefs about the market and how best to profit from it are personal preferences. If more people realised this, there’d be far less arguments between investors.

Here I’ll disclose two of my core beliefs that governs my investing rules and behaviour.

Belief 1: A low-fee market index fund is the only genuine "buy-and__-hold forever" stock market investment.

I can extend this belief to most smart-β funds provided the underlying portfolio is reasonably diversified across industry sectors. I believe a market index fund is as close to an autopilot "set-and forget" strategy as you can get because this type of fund is a self-organising, self-maintaining entity. On rebalance date, successful fast growing small companies will enter the index at the expense of the laggards who are purged. A long-term investor only requires the power to "invest regularly, sit down and do nothing". The S&P SPIVA scorecard shows that almost 90% of active funds fail to beat the market averages over the long term. This makes a broad market index fund a good long-term bet.

Belief 2: Buying an individual company stock is a long-term trade with an indefinite end date.

This belief has probably been forged through years of developing a trader’s mindset. Fundamental investors buy a company stock to acquire a fractional ownership in the underlying business. You hope to hold this individual stock for whole lifetime, or at least multiple decades, but there’s never any guarantee. Empires rise and fall. You don’t want to be holding a stock during the latter stages of its business cycle from hyper-growth phase, to industry stalwart, to declining laggard.

Individual stocks require a system of monitoring. Companies can sow their own seeds of decline, whether it’s a strategic misstep, a bloated organisational structure or a failure to recognise shifts in the marketplace. I hope to invest in a great business during its long and prosperous growth phase and exit when the business clearly slips into secular decline. Only the best businesses can stave off the deterioration phase. These businesses might they sell essential products and services and have a wide-enough moat to keep competitors at bay, or they may rejuvenate the business by opening new markets and pivoting their business models to stay relevant. Some businesses might be lucky enough to operate in industries that evolve at glacial pace.

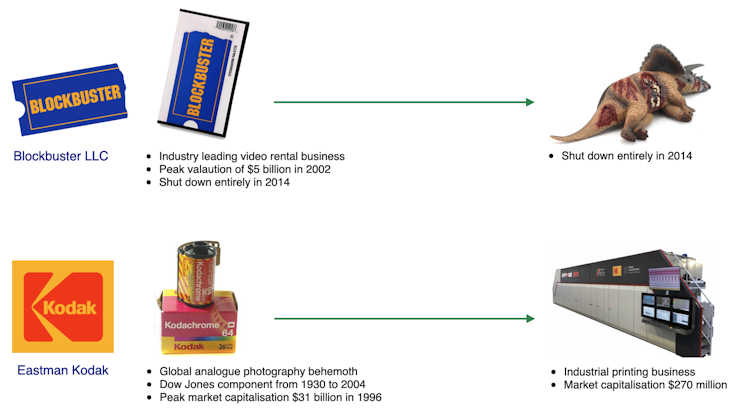

Blockbuster Video was the undisputed market leader in the video rental business. It failed to respond to the convenience of streaming movies digitally over the internet and consequently went bankrupt.

Netflix became a key player in the physical DVD home delivery service, but recognised the potential of streaming services and disrupted its own business model. Not satisfied, Netflix again disrupted its own business model to become an original content creator as it acknowledged the risk of studios having too much restrictive powers over platform providers.

Eastman Kodak (Original Ticker: EK) is a textbook case of falling victim to technological disruption. From its inception in 1888, Kodak became the dominant brand in analogue cameras, photography paper and processing. At its peak, Kodak controlled 70% of the US photographic film market.

Steve Sasson, an electrical engineer at Kodak, invented the digital camera in the mid-1970s. He developed the system of electronic components that could capture an image and display it on a screen without the need for physical film media. Unconvinced, the executives at Kodak failed to understand the significance of this digital film-less technology, fearing it would just endanger its current analogue photography business.

By the mid-1990s, Kodak’s competitors began releasing mainstream digital cameras in increasing numbers, relegating analog film processing to the realm of traditionalists and enthusiasts. Kodak became the victim of its own innovation. The executives failed to exploit the potential of being a first-mover advantage. Their reluctance to evolve their own business model is a cautionary tale of executive passivity and lack of foresight.

Eastman Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in January 2012, delisting from the New York Stock Exchange. In September 2013, Eastman Kodak re-emerged from bankruptcy and re-listed on the stock exchange (New Ticker: KODK) after issuing new shares. It survives as an industrial printing company.

The following quote from Morningstar’s authors of the book "Why Moats Matter" provides excellent description of a great business:

"So what's a great business? Essentially, we think it's one that can fend off competition and earning high returns on capital for many years into the future - increasing earnings, returning cash to shareholders, and compounding intrinsic value"

Heather Brilliant & Elizabeth Collins

Morningstar

As good as this description is, I would add a phrase to include the ability for a company to pivot its own business model to adapt and evolve in lockstep with its evolving marketplace.

A lot of incumbent companies don’t see disruption coming. When they finally do, they’re not agile enough to respond. Investors need to be eagle-eyed to spotting upcoming innovations and trends that might threaten the businesses we own. We need to be alert to what’s on the horizon and assess whether it’s consequential or not. Then we need to monitor whether the company executives respond accordingly. This all takes effort. Individual stock ownership is not a passive affair.

In the book "How Google Works", Google executives Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg assert "the pace of change is accelerating". This is exacerbated by faster adoption rates to new technology and new concepts. In the United States, it took 75 years for the landline telephone to reach 50 million users. For the same 50 million user milestone, it took airplanes 68 years, lightbulbs 46 years and television 22 years.

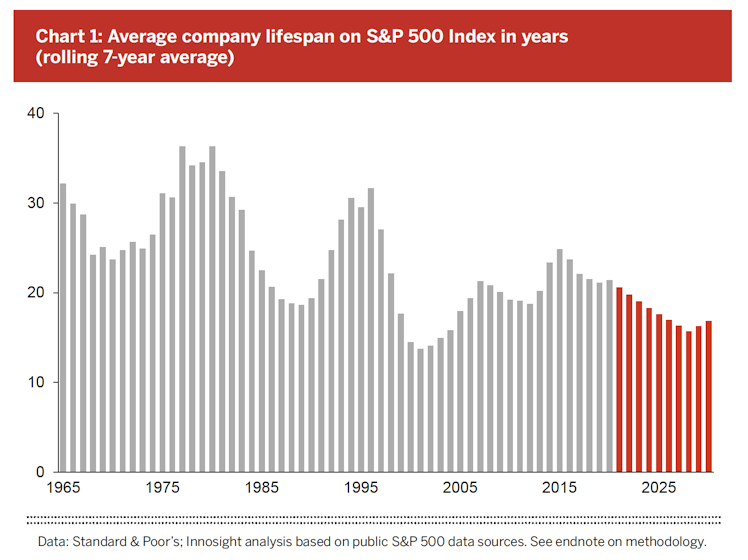

The theme of rapid change is well documented. Over the last 50 years, the rate of change to the business landscape has accelerated. Innovation and disruption is occurring at a faster pace and companies who are slow to adapt will become extinct like the dinosaurs. We can look at the composition of the S&P 500 index which has experienced faster turnover in its stock constituents.

"A recent study by McKinsey found that the average life-span of companies listed in Standard & Poor’s 500 was 61 years in 1958. Today, it is less than 18 years. McKinsey believes that, in 2027, 75% of the companies currently quoted on the S&P 500 will have disappeared"

Professor Stéphane Garelli

December 2016

The following chart from research firm Innosight shows the declining lifespan of companies belonging to the S&P 500 index:

The average tenure of companies in the S&P 500 index in 1964 was 33 years. By 2016, the average tenure shrink to 24 years, a 25% decline in tenure. Innosight predicts the average tenure to continue to shrink as creative destruction, emergent industries and corporate mergers and acquisitions continue at pace.

"Our latest analysis shows the 30- to 35-year average tenure of S&P 500 companies in the late 1970s is forecast to shrink to 15-20 years this decade"

We want to avoid holding stock in a business during its own death march. Holding a stock all the way up for years, or even decades in some cases, only to watch it fall all the way down to your cost basis is an awful feeling. Unfortunately the endowment effect is a powerful bias. I have been guilty several times of holding on to a business for far too long.

Successful investors have a definitive exit strategy to avoid the painful "popcorn trade" where years of capital gains evaporate right in front of your eyes. The downside can be selling too early and leaving enormous amounts of future gains on the table. Companies can stage a comeback. If I’m wrong and I haven’t found a better opportunity for our capital, I can always buy back the stock … ego allowing.

What I’ve described is the "buy-to-hold" mantra rather than "buy-and-hold" mantra. I first came across this terminology from Scott Phillips, Chief Investment Officer of Motley Fool Australia. He admits to not remembering where he got it from originally, but the intent of the phrase is to counter the "never sell no matter what" mindset.

Conor Mac @investmenttalkk drew my attention to this excellent quote from Todd Wenning from Ensemble Capital:

"There's no such thing as buy and hold with equities because CORPORATIONS ARE ORGANISMS operating in ecosystems and, as such, are changing internally and responding to external stimuli. You can buy and hold something static like a painting or gold, but not equities"

In a nutshell, my belief is you "buy-and-hold" a market index fund, and "buy-to-hold" an individual company stock. An individual company stock will require the effort of regular monitoring and reevaluation, while market index funds are zero effort, only requiring lazy sitting power. I can excel at that.

X (formerly Twitter)

Conor Mac (@InvestmentTalkk) on X

I never took bio.

Already have an account?