Trending Assets

Top investors this month

Trending Assets

Top investors this month

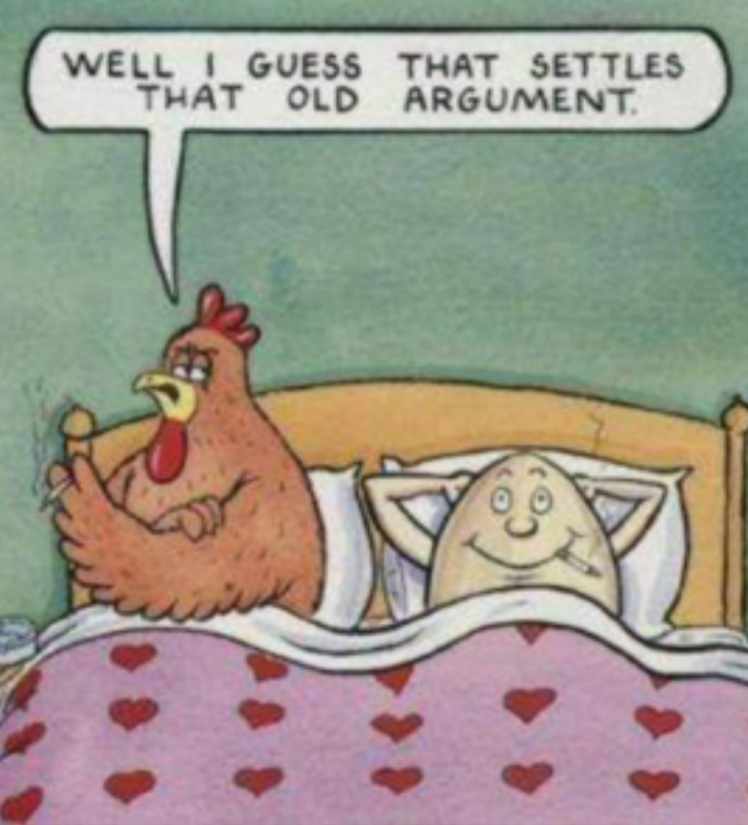

Life's Eternal Mysteries: Chicken or the egg? Buybacks or dividends?

Some questions in life seem destined to remain unanswered. Which came first, darkness or light? The chicken or the egg? And why exactly did that chicken cross the road? Perhaps the most heated debate of all, which may never be resolved:

WHICH PROVIDES A BETTER RETURN TO SHAREHOLDERS - DIVIDENDS OR BUYBACKS?

On this week's High Energy Tuesday Twitter spaces session, COM has invited me to discuss NCIB’s (Normal Course Issuer Bids aka “Buybacks”), which meant I had a little homework assignment.

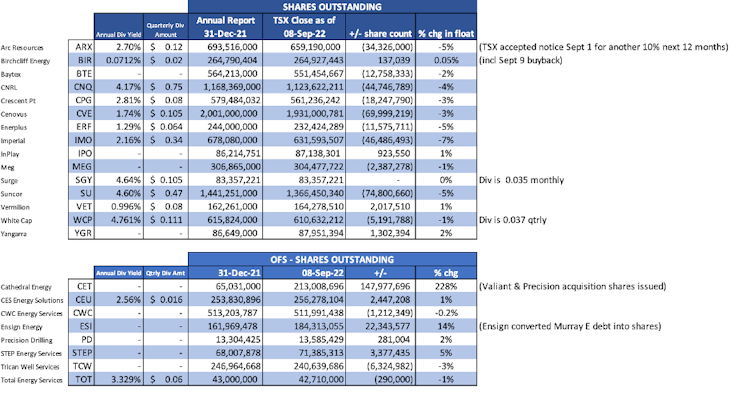

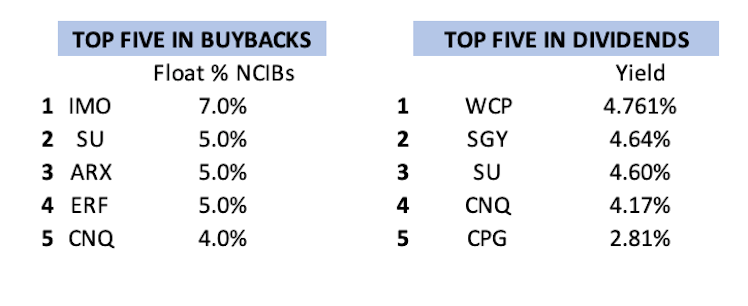

- Which of the COM favourites had the largest percentage of float buybacks from the end of last year until now?

- Which companies had increased the size of their float despite buybacks?

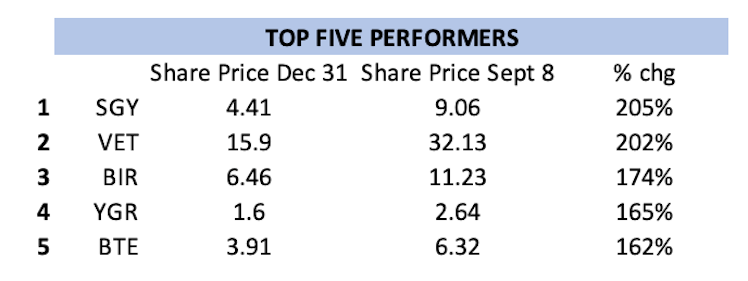

I must admit, the results left me rather perplexed. After hours of debate – no, scratch that – DAYS of debate, witnessed in my Twitter timeline over which was a better return to shareholders, surely my homework assignment would indicate the clear winner of the argument. With $CNQ placing in the top five for both buybacks and dividends, one would assume they would rightfully earn their place in the top five performers in share price? Hold onto your COM hats, because that assumption would be incorrect.

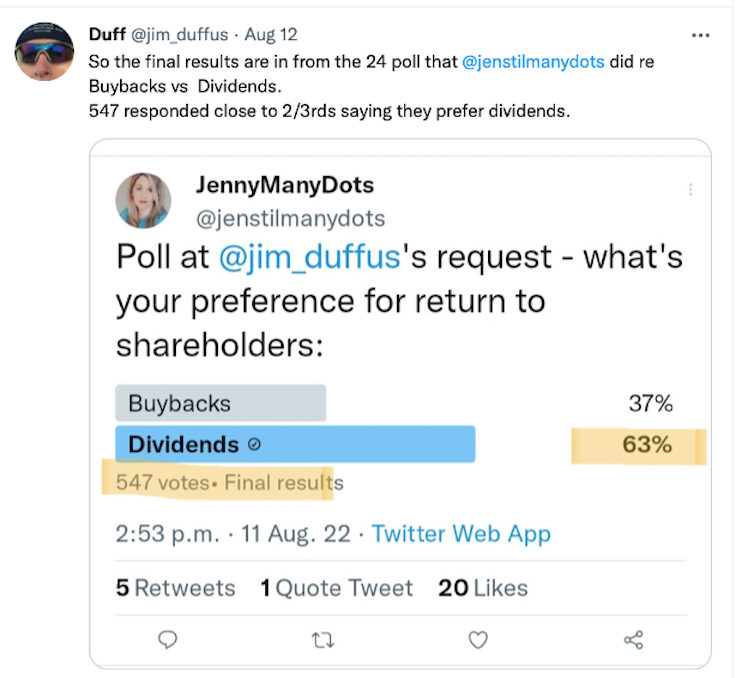

In a poll that Jim Duffus and I conducted on August 11, the choice among shareholders became clear. Almost two thirds of shareholders preferred the return of capital in the form of dividends.

According to Investopedia, five of the primary reasons why dividends matter for investors include:

- Substantial increase in stock investing profits

- Provide an extra metric for fundamental analysis

- Reduce overall portfolio risk

- Offer tax advantages

- Help to preserve the purchasing power of capital

So why would there be a minority stubbornly insisting that buybacks are a better option when clearly dividends offer multiple benefits? It turns out they have a reasonable argument, though Investopedia could only come up with four primary reasons rather than five. These included:

- Improved shareholder value (by reducing the number of outstanding shares & maintaining the same level of profitability, EPS will increase)

- Boost in share prices (simple supply and demand - when there is a less available supply of shares, then an upward demand will boost share prices)

- Tax benefits (shareholders could defer capital gains if share prices increase)

- Utilize excess cash (if a company has excess cash, then at worst the investors do not need to worry about cash flow problems; it signals to investors that the company feels cash is better used to reimburse shareholders than reinvest alternative assets - this supports the price of the stock and provides long-term security for investors)

The Downside of Buybacks

While investors tend to adore buybacks, there are several disadvantages investors should be aware of. Buybacks can be a signal of the market topping out; many companies will repurchase stocks to artificially boost share prices.

Typically, executive compensations are tied to earnings metrics and if earnings cannot be increased, buybacks can superficially boost earnings. Also, when buybacks are announced, any share price increase will typically benefit short-term investors rather than investors seeking long-term value. This creates a false signal to the market that earnings are improving due to organic growth and ultimately ends up hurting value.

Are Buybacks Good for Investors?

A buyback can be good for investors because they receive their capital back and are often paid a premium over the stock's market price. In addition, there is a boost in the share price for investors that still hold onto the stock; however, buybacks aren't necessarily always good for investors. Buybacks falsely inflate the share price, meaning the boost is temporary. Also, buybacks may not always be the best use of capital for a company, which may hurt its value down the road, adversely impacting investors.

The Risks to Dividends

During the Great Financial Crisis, almost all the major banks either slashed or eliminated their dividend payouts. These companies were known for consistent, stable dividend payouts each quarter for literally hundreds of years. Despite their storied histories, many dividends were cut. In other words, dividends are not guaranteed, and are subject to macroeconomic as well as company-specific risks.

Another potential downside to investing in dividend-paying stocks is that companies that pay dividends are not usually high-growth leaders. There are some exceptions, but high-growth companies usually do not pay sizable amounts of dividends to its shareholders even if they have significantly outperformed most stocks over time. Growth companies tend to spend more dollars on research and development, capital expansion, retaining talented employees and/or mergers and acquisitions. For these companies, all earnings are considered retained earnings, and are reinvested back into the company instead of issuing a dividend to shareholders.

It is equally important to beware of companies with extraordinarily high yields. As we have learned, if a company's stock price continues to decline, its yield goes up. Many rookie investors get teased into purchasing a stock just based on a potentially juicy dividend. There is no specific rule of thumb in relation to how much is too much in terms of a dividend payout.

A Matter of Personal Preference?

If the “dividends versus buybacks debate” comes down to personal suitability for the individual investor, is there actually a way to quantify which is a more successful strategy overall?

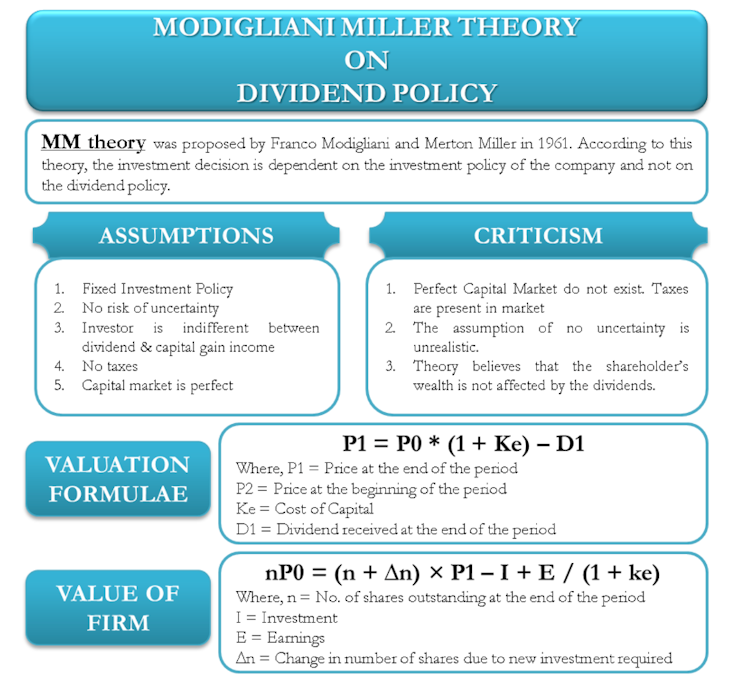

Let’s have a look at the “Modigliani-Miller Payout Irrelevance Theorem”.

In its most simplistic form, this theory proved that “in a perfect market” it doesn’t matter if companies do buybacks or dividends because it’s the same piece of a pie.

The five assumptions of the MM Theory are:

Perfect capital markets

It assumes that all the investors are rational, they have access to free information, there are no flotation or transaction costs, and no large investor to influence the market price of the share.

No Taxes

There is no existence of taxes. Alternatively, the tax rate for both dividends and capital gains is the same.

Fixed Investment Policy

The company does not change its existing investment policy. It means whatever may be the dividend payment, the company will invest as it has already decided upon. If the company is going to pay more amount of dividends, then it will have more equity shares and vice versa.

No Risk of Uncertainty

All the investors are certain about the future market prices and the dividends. This means that the same discount rate is applicable for all types of stocks in all time periods.

Investor Indifference Between Dividend Income & Capital Gain Income

It means if he requires the total return of Rs. 500, he may get Rs. 200 dividend income and Rs. 300 as capital gain income or reverse. In either of the case, he gets equal satisfaction.

Therefore:

The only thing that impacts the valuation of a company is its earnings, which are a direct result of the company’s investment policy and future prospects. So, according to this theory, once the investor knows the investment policy, he will not need any additional input on the company’s dividend history.

MM theory goes a step further and illustrates the practical situations where dividends are not relevant to investors. Irrespective of whether a company pays a dividend or not, the investors are capable enough to make their own cash flows from the stocks depending on their need for the cash. If the investor needs more money than the dividend he received, he can always sell a part of his investments to make up for the difference.

This theory also believes that dividends are irrelevant by the arbitrage argument. By this logic, external financing offsets the dividend’s distribution to shareholders. Due to the distribution of dividends, the stock price decreases and will nullify the gain made by the investors because of the dividends.

If MM was correct, then dividends should be deemed irrelevant. One could argue against all five assumptions of the MM Theorem but its weakest point may be that of a “perfect capital market” existing. For that, let’s turn to the Theory of Efficient Markets.

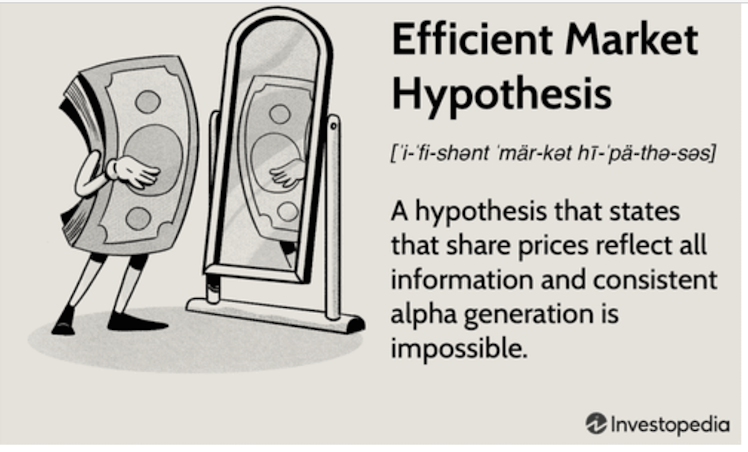

The Efficient Market Hypothesis

The efficient market hypothesis, alternatively known as the efficient market theory, is a hypothesis that states that share prices reflect all information and consistent alpha generation is impossible. According to the EMH, stocks always trade at their fair value on exchanges, making it impossible for investors to purchase undervalued stocks or sell stocks for inflated prices. Therefore, it should be impossible to outperform the overall market through expert stock selection or market timing, and the only way an investor can obtain higher returns is by purchasing riskier investments.

Although it is a cornerstone of modern financial theory, the EMH is highly controversial and often disputed. Believers argue it is pointless to search for undervalued stocks or to try to predict trends in the market through either fundamental or technical analysis.

Investors such as Warren Buffett have consistently beaten the market over long periods, which by definition is impossible according to the EMH.

Detractors of the EMH also point to events such as the 1987 stock market crash, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell by over 20% in a single day, and asset bubbles as evidence that stock prices can seriously deviate from their fair values.

If efficient markets cannot exist, then MM’s theory that dividends are irrelevant becomes irrelevant itself.

Harvard professor John Lintner and American economist Myron Gordon developed the bird-in-hand theory as a counterpoint to the Modigliani-Miller Theory.

Under the bird-in-hand theory, stocks with high dividend payouts are sought by investors and, consequently, command a higher market price.

Investing in capital gains is mainly predicated on conjecture. An investor may gain an advantage in capital gains by conducting extensive company, market, and macroeconomic research. However, ultimately, the performance of a stock hinges on a host of factors that are out of the investor's control.

For this reason, capital gains investing represents the "two in the bush" side of the adage. Investors chase capital gains because there is a possibility that those gains may be large, but it is equally possible that capital gains may be nonexistent or, worse, negative.

Legendary investor Warren Buffett once opined that where investing is concerned, what is comfortable is rarely profitable. Dividend investing at 5% per year provides near-guaranteed returns and security. However, over the long term, the pure dividend investor earns far less money than the pure capital gains investor. Moreover, during some years, such as the late 1970s, dividend income, while secure and comfortable, has been insufficient even to keep pace with inflation.

Much like humanity will never know if that egg came first or if it was indeed the chicken, I’m afraid the mystery of ‘dividends or buybacks as a greater return to shareholders will forever elude even the greatest minds among us, apologies QE Buble...

Investopedia

Bird In Hand: Definition as Strategy in Investing and Example

Bird in hand is a theory that postulates that investors prefer dividends from stock to potential capital gains because of the inherent uncertainty in capital gains.

Already have an account?